2007

11 x 8 1/2 inches

graphite, ink and ink wash on graph paper

“Our dreams could have ended in the spring of 1983.

We escaped a Chamberlain moment. A jerk of the wheel in the wrong direction and the French-chocolate Mercedes would have sculpturally moshed with a faded emerald/pink-splotched Plymouth in a high-speed, head-on collision.

It would have been terrible. The empress of Empire of Light and high priestess of a collection holding things divine and surreal, in a demolition-derby confrontation with a wannabee museum worker chasing minimum wages to support his own grandiose ideas, sometimes mixed with meaningful aspirations. Everything almost reduced to French and Asian forensic co-mangling flesh, along with rubber and steel, German electronic components and a rebuilt Detroit voltage regulator.

It was like this.

I had started work for the Rice Museum as the new prep person. I was assigned the less glamorous, non white-glove handling jobs, like solo demolition of the drywall cathedrals of closed exhibitions. The inevitable tetanus shot was worth it for an occasional glimpse of surreal stuff. Her fabulous collection and accompanying scholarship clarified misconceptions nurtured by the dusty books of simplified college art history. The dust stirred up by my labor aroused new configurations and delusions… one day I would have walls built like this for my one-person exhibition.

That morning was a one-person unloading of massive crates, cradling the finest and most curious aged cultural artifacts. All done, I approached the crew who had been inside the museum smoking and philosophizing. I bummed a smoke as they strolled out of the museum like a Phillip Morris version of Raphael’s School of Athens…cigs dangling, making challenging statements in reference to the human condition.

I got some cold coffee, slumped on a crate, propped my feet and lit up. As the match sulphur lingered, she came in.

Dominique made a straight agitated gait toward me, “No, no, Noooo, NOOO…You will burn up my entire museum!” Her small frame and massive credentials lorded over me with finger-wagging emphasis. Face to face with Dominique, I dunked the danger, stirring the coffee with the butt.

We both weren’t happy, but it was almost noon and time for a beer.

It was 3:30 before I came wheeling back from lunch. I wanted to stay clear of the museum until she left. I’d been dressed down by the grand dame, but I put away enough drinks to put away feeling bad. Sunglasses on and acuity off, I leaned back, rested my eyes, and started cutting across the asphalt expanse of the Rice University stadium parking lot, blind.

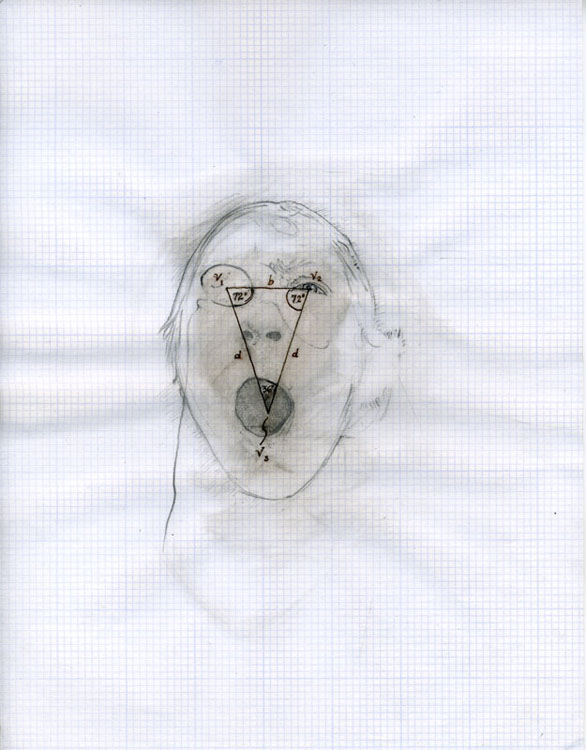

I opened my eyes to her oncoming car. Her mouth was a dark silent “O” that matched her green-glass specs. They formed a perfect triangulation, a geometry that reminded me of her excited exclamation at a staff meeting regarding a table, “But a plane is defined by three points!” The math of my face was not much different. Probability sided with our choices of trajectory as we slid apart without scratch or chrome souvenir scrap. I kept driving. I didn’t look back; neither did she.

Assuming a pink slip the next day, I tried to avoid her when she came in. She found me. Her hard, determined look pried my downcast head up and she emphasized: “We must be vigilant!” That was it and I wasn’t fired. It suggested our escape from collision would set things up for a rematch.

The exhibition she granted me in the spring of 1991 was a prodigal moment. I had abandoned my shiftless ways. It was my immersion in creating new artwork unfashionably focused on tragic political realities and arcane meanings that heralded this return to grace. It was a supreme honor that the dark light of these works was accepted into the prism held by Dominque DeMenil.

Before the opening we had lunch together at her home. It was a table for four. Walter Hopps, Paul Winkler, Mrs. D, and myself. The lunch began with Mrs. D in collector mode overdrive. An expert orchestra of actions and events had to be developed to wrest a Seurat she wanted from a reluctant-to-part-with owner. Walter laid down the hard facts as Mrs. D worked the corners for any weakness. The cost would be staggering, but the desire for the work was definitive.

She suddenly steered away from accumulation to protest against those who would engineer the paths of human misery. We spoke of the difficult job of exposing the perps of unjust sufferings.

She eyeballed me with that familiar, hard, even look. She said, “We must be vigilant! “

Her pronouncement hinted at a recollection of our crash course years earlier, but this time disapproval transmuted into a smile of elegant camaraderie and survival.”

-Mel Chin, “Mrs. D and Me.” Printed in Art and Activism: Projects of John and Dominique de Menil, Laureen Schipsi, ed., The Menil Collection, Houston, TX, 2010